Ashford Mine, Black Mountains, Death Valley

The Ashford Mine and Mill's history is a tale of ambition, persistence, and the harsh realities of gold mining in Death Valley. Discovered by Harold Ashford in 1907 after noticing unworked claims by the Keys Gold Mining Company, Ashford took over these claims and after a legal battle, retained them in 1910. Despite initial lack of success, the Ashfords managed to lease the mine in 1914 to B.W. McCausland and his son, who invested heavily in the infrastructure, including a mill on the valley floor, indicating the scale of their ambition. The McCauslands envisioned a prosperous operation, driving a tunnel 180 feet into the mountain and employing twenty-eight men at the peak of activity.

However, the venture quickly soured as the ore extracted did not yield enough value to cover the extensive capital investments. By September 1915, just a year after significant improvements were made, the operation ceased due to financial unviability, and the McCauslands opted out of paying the lease, leading to another unsuccessful lawsuit for the Ashfords. The mill, built to support a much larger operation, was never used again after 1915, standing as a relic of overambition in the harsh desert.

The mine lay dormant for several years, seeing only sporadic activity which never amounted to significant production until 1935 when the Golden Treasure Mines, Inc., took a lease. This company attempted to revive the mine by only extracting high-grade ore due to the prohibitive costs of long truck hauls required to reach processing facilities. This phase of operations was short-lived, ending in 1938 with minimal success, further emphasizing the challenges of mining in such a remote and unforgiving environment.

After a brief period of working the mine themselves and making a minor shipment in 1938, the Ashfords leased it out once more to Bernard Granville and Associates of Los Angeles in the late 1930s. The new lessees introduced an aerial tramway to streamline operations, but like their predecessors, they too ceased operations by 1941 without any notable success. This pattern of brief attempts at revival followed by disappointment was characteristic of the mine's operational history.

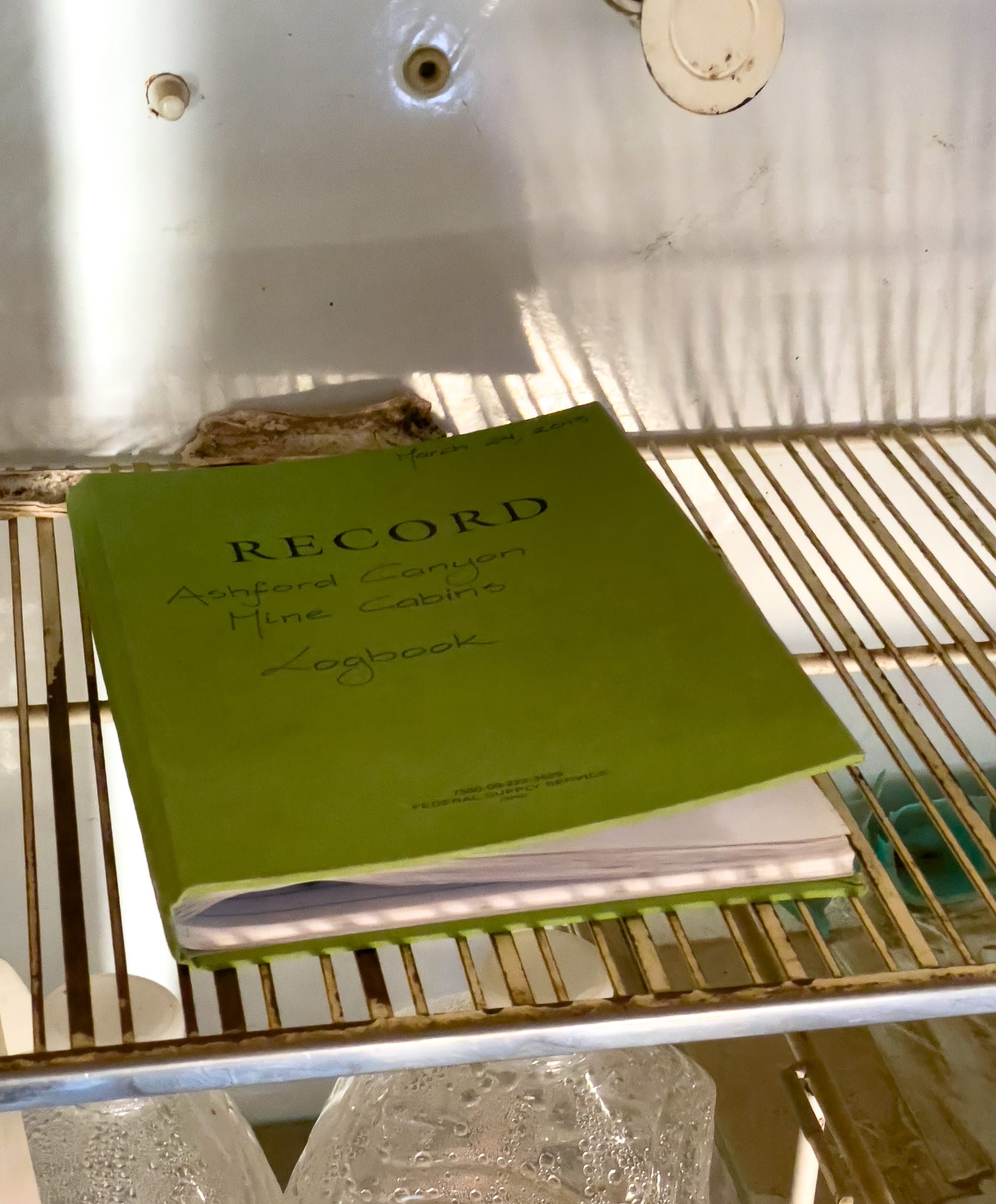

At the Ashford Mine, the remnants of a once-thriving mining operation cling to the rugged slopes of the Black Mountains, providing a glimpse into the past albeit without the distinction of historical significance as defined by the National Register. The main site, accessible only through a strenuous hike, hosts a variety of dilapidated structures dating from the 1930-1940 mining period, including a collapsed shack, an outhouse, a large office and cookhouse building, wooden bunkhouses, a tin shed, a headframe with an ore bin, and tramway towers. These structures paint a vivid picture of life in a small mining community of that era, illustrating the day-to-day workings and the isolated existence of its inhabitants, though their historical contributions are considered limited.

Just a short distance away on the eastern side of the knoll, the scene shifts to an older section of the mining site, likely from the McCausland's efforts in the 1910s. This area, characterized by a few older adits, dumps, and the remains of a collapsed shack alongside several leveled sites once occupied by tents, offers a more intact snapshot of earlier mining activities. Despite its better preservation and the clearer historical narrative it provides, this part of the mine also lacks the criteria needed for National Register significance. The recommendation for both these areas is one of benign neglect, acknowledging their potential value for historical archaeological research while accepting their current state of natural decay.

The story of the Ashford Mine encapsulates the boom and bust cycles typical of gold mining in the early 20th century, particularly in challenging locations like Death Valley. It's a narrative of initial hope, heavy investment, and eventual defeat by economic and geological realities, leaving behind structures like the Ashford Mill as monuments to the enduring hope and transient grief of the gold rush era.