Stacks, Sticks, and Brass: A Field Guide to Survey Marks

Not far from the crumbling remains of the Confidence Mine, I wandered through the sunbaked emptiness of Death Valley. The wind moved through the canyons, whispering like it had stories to tell—maybe about the miners who once chased their fortunes here, maybe just about the heat. I wasn’t looking for gold, just a piece of history, something left behind. After a few hours of picking my way through the barren Talc Hills, I crested a ridge, and there it was: USLM 72.

At first glance, it isn’t much to look at—just a weather-beaten wooden post, leaning ever so slightly, standing atop a five-foot pile of hand-stacked rocks. A cairn, anchoring it against time, erosion, flash floods, and the relentless winds. It’s the kind of thing you’d miss if you weren’t paying attention, but for those who know what they’re looking at, these old United States Location Monuments (USLMs) are more than just curiosities. They are anchors of certainty in a landscape defined by uncertainty.

The survey marker before me was more than just a lonely post in the desert—it was part of a vast and intricate system of land measurement, one that has been shaping the American landscape for over a century.

The History of Survey Markers in the U.S.

Land surveying has been a fundamental tool for expansion, settlement, and infrastructure development since the earliest days of the United States. As settlers moved westward, precise land measurements became essential for property rights, taxation, and major engineering projects like roads, railroads, and mines. The earliest survey markers were rudimentary—wooden stakes, stone cairns, or chiseled marks on rock formations, placed by local surveyors to establish property lines and reference points.

However, as the country grew, so did the need for a standardized, scientifically rigorous system of measurement. This led to the creation of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS) in 1807, one of the nation’s earliest scientific agencies. Their goal was to establish a nationwide geodetic network—a system of fixed reference points that could be relied upon for everything from land division to navigation.

The real transformation came in the 1920s, when the United States undertook an ambitious nationwide geodetic survey. This was the first large-scale effort to create an interconnected, continent-wide framework of benchmarks, designed to improve precision in mapping and engineering projects. The USC&GS (now the National Geodetic Survey) set tens of thousands of permanent benchmarks, often in remote and rugged locations. These markers were typically metal discs embedded in concrete or stone, stamped with unique identification numbers and elevation data.

Surveying back then required grit, precision, and patience. Before satellites and laser rangefinders, surveyors measured the land using chains—not metaphorical ones, but actual metal links, each 66 feet long, painstakingly stretched across hills, dry lake beds, and valleys. Two men, one at each end, would leapfrog their way across the landscape, marking distances 66 feet at a time. Every measurement mattered—each number on the surveyor’s log could become a railroad, a town, or just a name on a map. Even today, many of these benchmarks remain in use, their data incorporated into modern GPS systems.

Using triangulation, these benchmarks formed an invisible web of reference points, allowing future surveyors to establish accurate elevations and positions anywhere in the country. Mining operations, railroad expansions, and large-scale infrastructure projects depended on them. Without these benchmarks, engineers would have had no reliable way to measure distances, ensure level grades for rail lines, or establish property boundaries with certainty.

Survey Markers in the Field: USLMs, Benchmarks, and Mining Monuments

The USLM I found in the Talc Hills was just one piece of a much larger puzzle. The land is full of survey markers, each with its own purpose and history.

- United States Location Monuments (USLMs): Fixed reference points used in land surveys, especially in areas where the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) was incomplete.

- Benchmarks (BM): Small brass discs embedded in bedrock or concrete, stamped with elevation data, placed by agencies like the USGS and NGS to measure land elevation.

- Vertical Angle Benchmarks (VABMs): Specialized elevation markers, often found in steep terrain, used to record precise height measurements.

- Mining Claim Monuments: Wooden posts, rock cairns, or metal tags marking the boundaries of mining claims, placed by individual prospectors to legally stake a claim under the General Mining Act of 1872.

Together, these markers form an intricate web of history and geography, a system designed to impose order on the vast, untamed wilderness. Whether you’re a surveyor, a historian, or just someone who roams the backcountry with a sharp eye for detail, understanding these markers transforms the way you see the land.

Before we take a closer look at each type of survey marker, where to find them, and what they reveal about the history of the land beneath our feet, we need to understand the Public Land Survey System (PLSS).

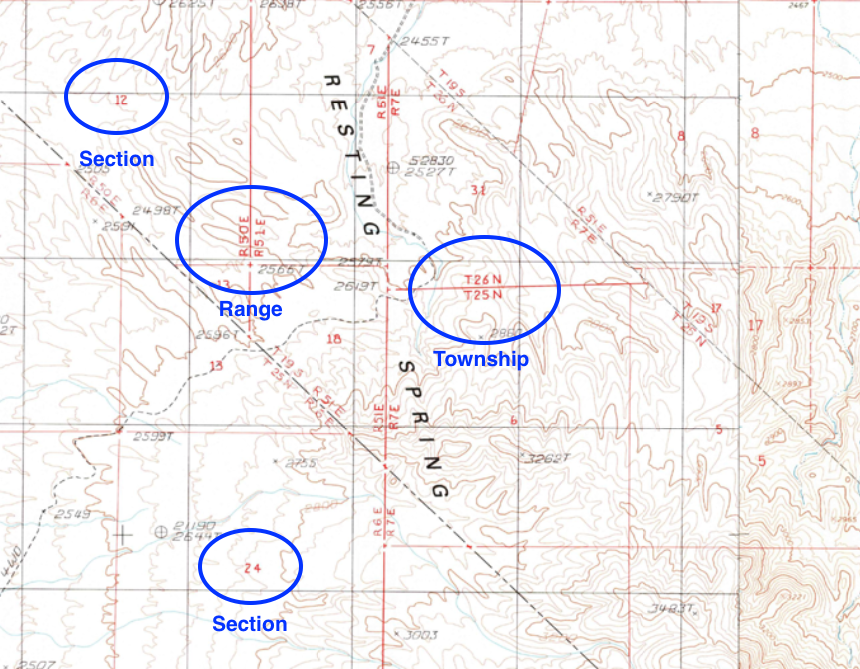

The Public Land Survey System (PLSS) – Dividing the West

To bring order to the vast, newly acquired lands of the United States, the federal government developed the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) in the late 18th century. This system, first implemented by the Land Ordinance of 1785, divided land into a standardized grid of townships and sections, making it easier to survey, sell, and distribute land for settlement, agriculture, and industry.

Under the PLSS, land was divided into townships, each measuring 6 miles by 6 miles. These were further broken down into 36 numbered sections, each 1 square mile (640 acres). Sections could then be subdivided into smaller plots for homesteaders, ranchers, and businesses. This system was the foundation for land ownership and development across much of the western United States.

However, the PLSS had its limits. Mountainous terrain, irregular landscapes, and existing Spanish or Native land claims often made the standard grid impractical. In these cases, surveyors relied on special markers, like United States Location Monuments (USLMs), to define land boundaries. This is why places like Death Valley, Nevada’s mining districts, and parts of the Southwest often have irregular land parcels and survey markers instead of clean township grids.

Even today, property lines, land records, and legal descriptions in much of the U.S. still rely on the PLSS, making it one of the most enduring legacies of early American land management.

USLM & USMM

Survey markers in the American West come in many forms, but two that frequently appear in historical land records and mining regions are United States Location Monuments (USLMs) and United States Mineral Monuments (USMMs). While they may look similar in the field—often appearing as weathered wooden posts, stone cairns, or brass caps—their functions were distinct.

United States Location Monuments (USLMs) – Survey Control Points in Remote Areas

Purpose:

USLMs were established as fixed reference points for land surveys in areas where the standard Public Land Survey System (PLSS) was incomplete or difficult to implement. They provided stable starting locations for future land divisions, including mining claims, homesteads, and other public land allocations.

Key Characteristics:

- Usually found in rugged, remote areas where PLSS section corners were not practical.

- Assigned a USLM number, recorded on government survey plats and maps.

- Constructed as wooden posts, stone cairns, or brass caps, depending on the time period.

- Often accompanied by survey notes detailing its location and purpose in land office records.

Where to Find Them:

- Mining districts and remote land surveys, especially in areas where PLSS grids were incomplete.

- Recorded on old General Land Office (GLO) plats, available through the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

- Field locations marked by cairns or wooden posts, though many have been lost to time.

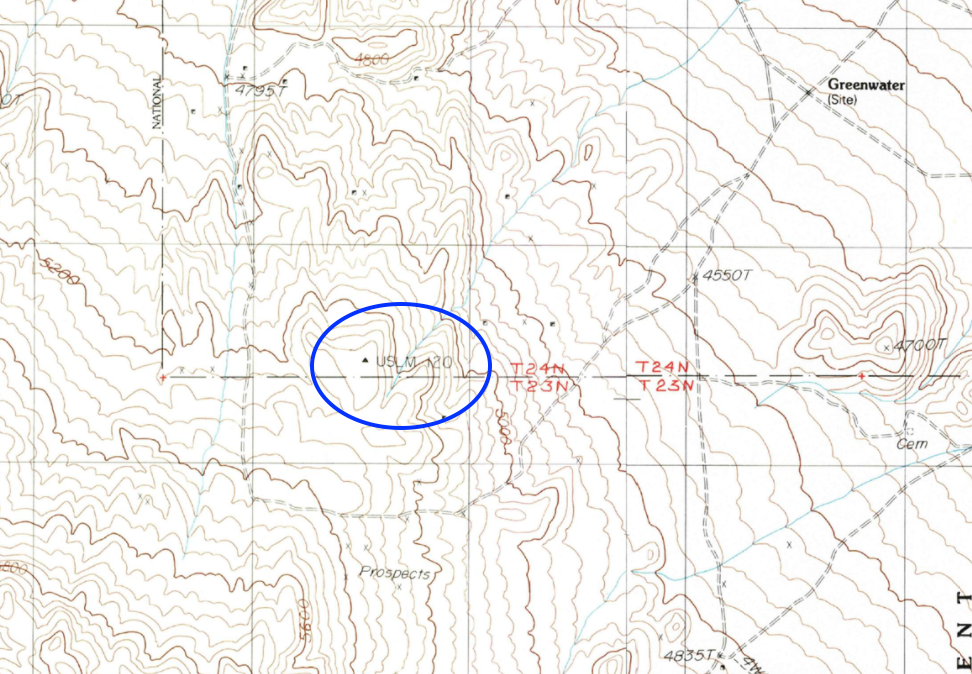

USLM 120 near the old Greenwater townsite in Death Valley. Notice the long wooden witness post on the ground. This USLM is circa 1907.

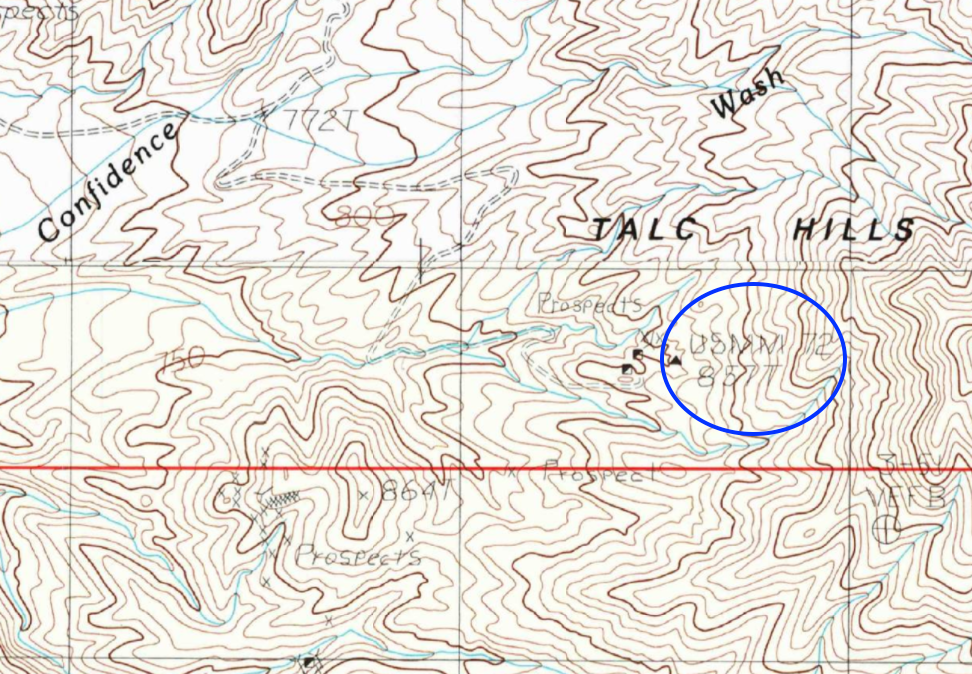

Notice that USLM 72 was originally a US Mineral Monument (USMM) and allowed for the mining claims along Confidence Wash to be accurately mapped. Today is a US Location Monument in very good condition as it was used during the 1994 boundary establishment for Death Valley National Park.

United States Mineral Monuments (USMMs) – Mining-Specific Survey Points

Purpose:

USMMs were specifically created for mineral surveys in regions where standard PLSS survey markers did not exist. Since many mining claims were located in irregular terrain, miners and surveyors needed reliable starting points to measure claim boundaries.

Key Characteristics:

- Used exclusively for mining claims, unlike USLMs, which were broader survey control points.

- Marked the starting point for surveying groups of mining claims rather than individual claims.

- Often found near historically significant mining districts, particularly where gold, silver, or other valuable minerals were extracted.

Where to Find Them:

- Near old mining claims and historic mining towns, particularly in areas with irregular land surveys.

- On mineral survey plats filed with the General Land Office (GLO) and BLM.

- In the field as cairns, brass caps, or posts, though many have disappeared due to erosion, vandalism, or land development.

Why These Monuments Matter Today

Though modern GPS-based surveying has largely replaced the need for USLMs and USMMs, these markers remain important for historical research, land boundary verification, and mining claim history. Some are still visible in the field, offering a glimpse into the methods used to divide and document the vast, uncharted territories of the past.

If you come across one, take a moment to appreciate it—it’s not just a marker, but a piece of history, a physical connection to the surveyors, miners, and land explorers who once relied on it to navigate an untamed landscape.

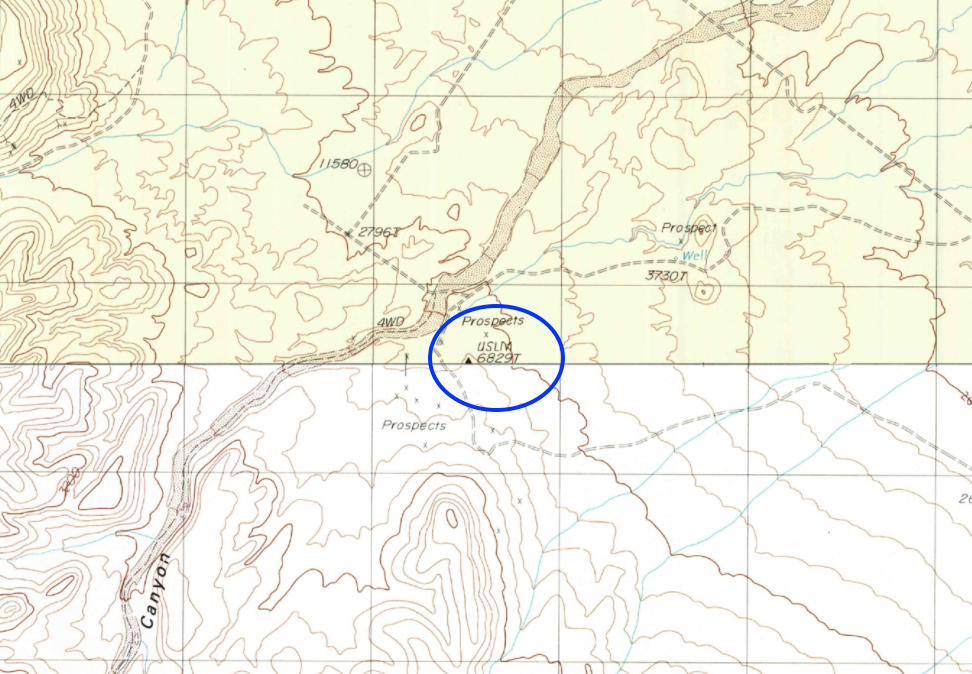

US Location Monument 6829T is confusing because it is stamped as a US Mineral Monument. This is critical monument as it is key survey mark for the enormous borate mining district that stretches from the Lila C Mine outside of Death Valley Junction all the way to the modern mine near Ryan. Along the way are subordinate marks (lower right photo) that allow for easier surveying than trying to come off 6829T directly.

Benchmarks (BM) & Vertical Angle Benchmarks (VABM) Explained

Surveying the land requires precise reference points, and two of the most common markers found across the American West are Benchmarks (BM) and Vertical Angle Benchmarks (VABM). These markers, usually small but significant, provide elevation data critical for mapping, engineering, and land management. Though often overlooked, they are essential pieces of the survey network that help define how we measure and understand the landscape.

Benchmarks (BM) – Fixed Elevation Reference Points

Purpose:

Benchmarks (BMs) are permanent survey markers used to establish known elevation points above sea level. They provide a stable reference for topographic maps, engineering projects, flood studies, and navigation.

Key Characteristics:

- Typically small brass or bronze discs embedded in rock, concrete, or metal posts.

- Stamped with elevation data and an identification number assigned by agencies like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) or National Geodetic Survey (NGS).

- Found at major survey points, along railroads, near dams, or in urban centers where precise elevation is necessary.

- Some are “First-Order Benchmarks”, meaning they have been surveyed with extremely high precision.

Where to Find Them:

- Marked on USGS topographic maps with an “BM” symbol and elevation.

- Along trails, roadways, and infrastructure projects, often overlooked by passersby.

- On mountain summits, ridgelines, and other significant land features to assist in elevation surveys.

- Online databases like the NGS Data Explorer, where many benchmarks are cataloged.

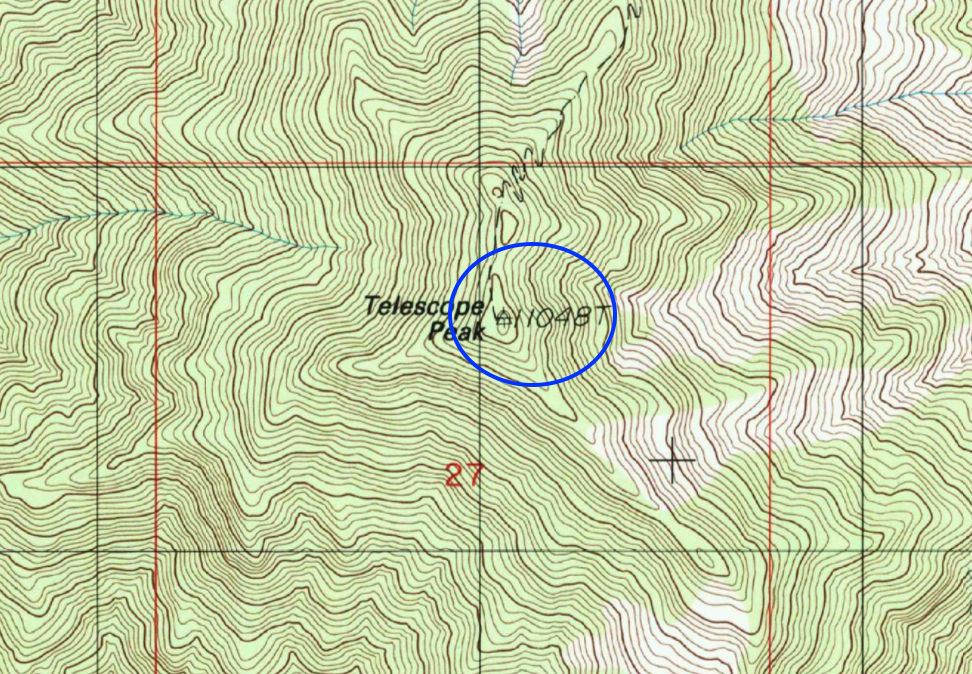

The benchmark atop Telescope Peak.

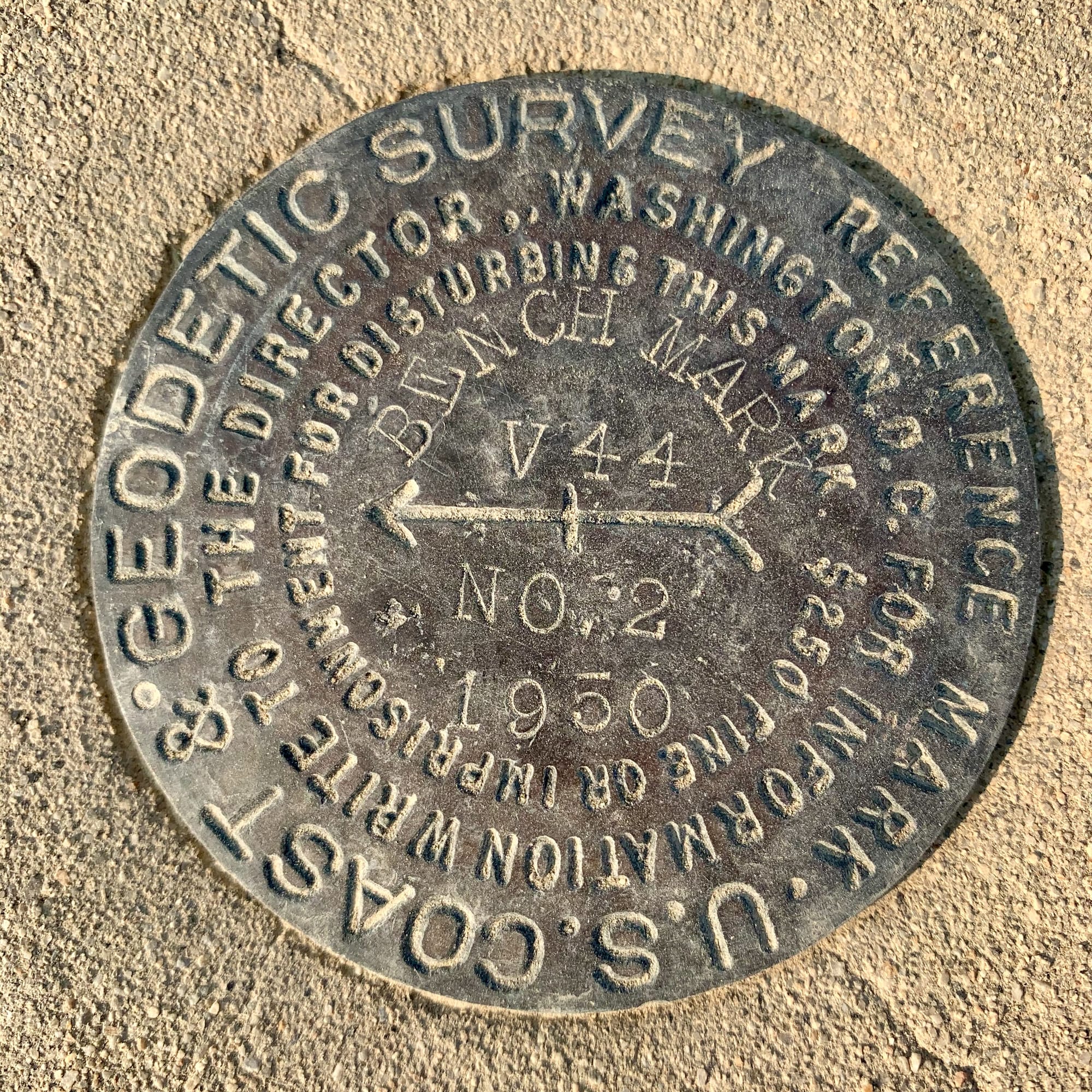

A Vertical Control Mark (VCM) that predates the current VABM name. This one is located at the mouth of Long John Canyon. It was first set as V44 in 1950. Due to excessive water extraction by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the land in Owens Valley has noticeably subsided resulting in V44 being reset in 1984.

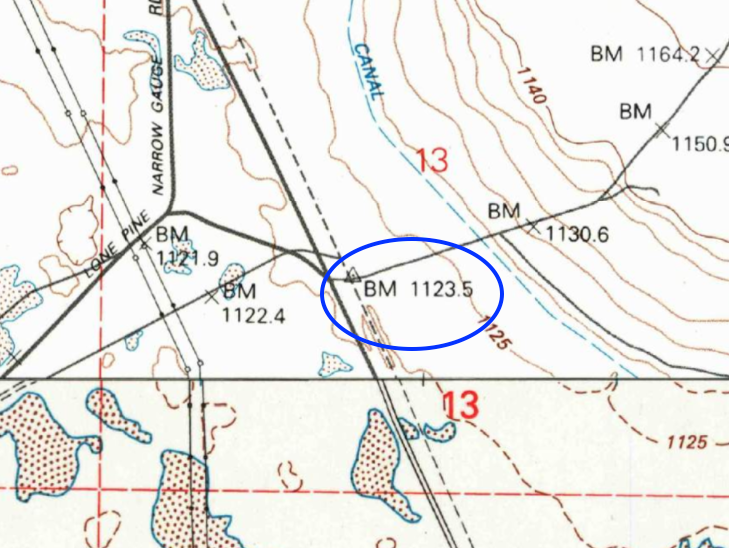

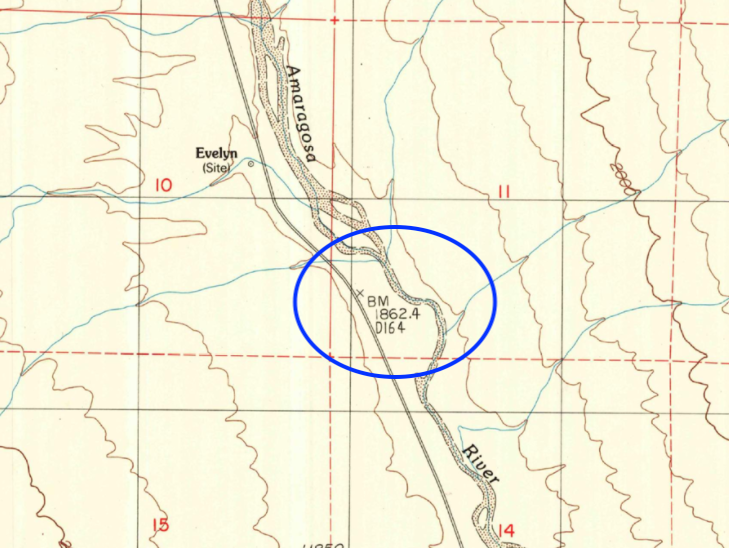

Notice the current topo map is more accurate than the 1933 benchmark D164. This is located along the former Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad right-of-way (now CA 127). In the right hand photo the original wooden witness post (more on those later) sits on the ground and a modern fiberglass witness post stands next to the BM.

Left: a lonely BM off an old wagon road near the Cottonball Basin. Right: A sad, unmaintained, benchmark that has been knocked off station by a flash flood on the floor of Death Valley.

Vertical Angle Benchmarks (VABM) – Elevation Points for Slope Measurement

Purpose:

Vertical Angle Benchmarks (VABMs) are a specific type of benchmark used to measure elevation at precise angles, particularly in rugged or steep terrain. They were crucial for surveying mountains, canyons, and other areas where traditional horizontal measurements were difficult to establish.

Key Characteristics:

- Similar in appearance to regular benchmarks (brass or bronze discs), but their primary use is for vertical angle calculations.

- Found in areas where elevation changes rapidly, such as steep canyons, cliffs, and high-altitude regions.

- Used in terrain modeling, infrastructure planning, and historical topographic surveys.

- Often referenced on older USGS maps and survey records, though many have since been superseded by modern GPS-based elevation data.

Where to Find Them:

- Marked as “VABM” on historical USGS topographic maps.

- In rugged areas with significant elevation changes, particularly in remote or mountainous regions.

- On historical survey logs, where they were recorded for geodetic and land development projects.

- Under a cover, many VABMs are protected via a small metal lid to further ensure protection from vandalism or natural movement.

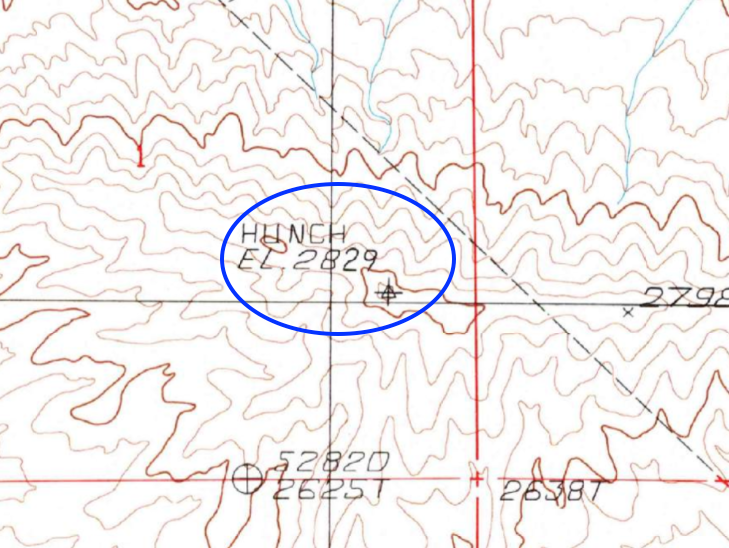

The HUNCH VABM outside of Ash Meadows placed in 1966. Notice the tilted witness post nearby (and the great view!)

Why These Markers Matter Today

While modern GPS and LiDAR technology have reduced reliance on traditional benchmarks, they are still crucial for surveying, geospatial research, and historical exploration. Many old benchmarks remain exactly where they were placed decades ago, quietly preserving data that is still useful today.

For hikers, surveyors, and history enthusiasts, finding a benchmark is like uncovering a hidden connection to the past, a tangible reminder of the effort that went into mapping the landscape we navigate today.

Mining Claim Markers

Throughout the mining regions of the American West, the land is scattered with old mining claim markers—the physical remnants of prospectors staking their legal rights to mineral-rich ground. These markers served as boundary references for mining claims, defining where one claim ended and another began.

Mining claim markers typically fall into two categories: Location Monuments, which established the initial claim, and Corner Monuments, which defined its boundaries. While many have weathered away with time, some still stand, silent witnesses to a bygone era of boomtowns and prospecting fortunes.

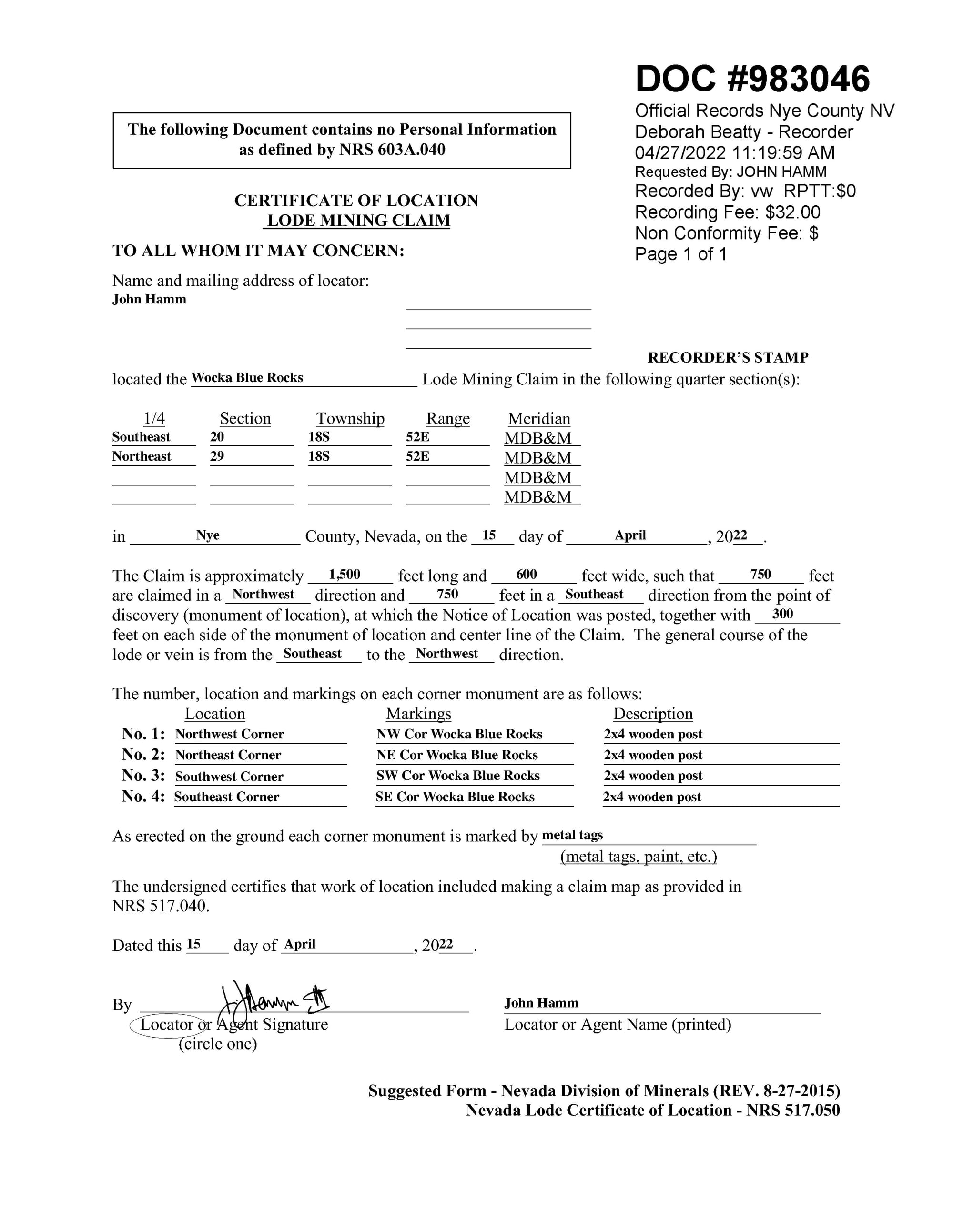

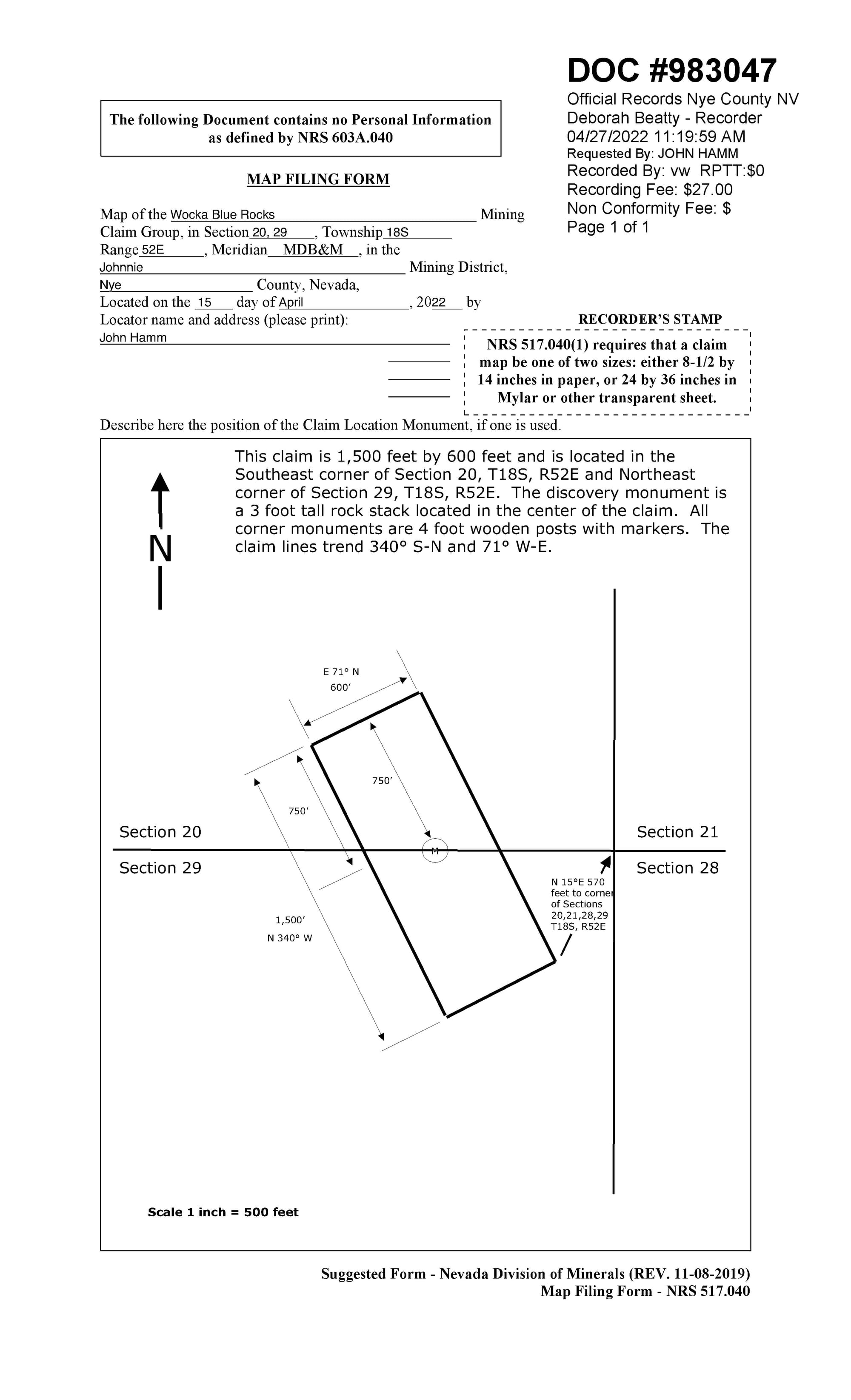

The Certificate of Location and Mine Map for my mining claim in the Johnnie Mining District north of Pahrump. Notice the use of the PLSS to describe the claim location, the description of the discovery monument, and the use of PLSS to describe the SE corner relative to the boundary between townships.

Location Monuments – The Heart of a Mining Claim

Purpose:

A Location Monument (sometimes called a Discovery Monument) was the first marker placed when a miner staked a claim. It served as the official point of discovery, marking where a prospector had found valuable minerals and intended to file a legal claim.

Key Characteristics:

- Often a wooden post, rock cairn, or metal stake, sometimes with a tin can or glass jar containing a written notice of location.

- Established by individual prospectors or mining companies to legally define a claim under the 1872 General Mining Act.

- Positioned at the most significant point of the claim—usually near a vein, outcrop, or placer deposit.

- Frequently referenced in county courthouse records and old BLM mineral survey plats.

Where to Find Them:

- Near old prospecting sites, historic mining camps, and abandoned mines.

- Documented on claim maps and mineral survey records from the General Land Office (GLO) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

- In some areas, modern prospectors and mining companies still establish location monuments when filing new claims.

Corner Monuments – Defining the Boundaries of a Claim

Purpose:

Once a claim was located, Corner Monuments were placed to define its physical boundaries. Under U.S. mining law, a claim (typically 20 acres per individual claim) had to be properly marked so that others could see and respect its limits.

Key Characteristics:

- Usually four corner posts or cairns, marking the rectangular boundaries of a claim.

- Some included “End Line” markers if the claim covered a lode or vein that extended in a straight line.

- Could be made of wooden posts, metal pipes, stacked stones, or old claim tags nailed to trees.

- Often included a written location notice, either attached to the marker or placed in a container nearby.

Where to Find Them:

- Surrounding an old mine or prospect pit, sometimes partially collapsed or buried under debris.

- Along ridges, slopes, or washes, where placer claims followed water channels.

- On historical mining claim maps, though many claims were abandoned or never formally recorded.

Why These Markers Matter Today

While many old mining claim markers have disappeared, they remain an important part of mining history. Some still hold legal significance, especially if a claim is actively maintained. Others are simply relics, their original notices long since decayed, standing as stoic reminders of the frenzied prospecting that once shaped the American West.

For modern explorers, stumbling across a mining claim marker is like uncovering a chapter from the past. Whether you’re hiking, researching old claims, prospecting, or simply admiring the remnants of a once-thriving industry, understanding these markers adds depth to the landscape, turning a pile of rocks or a leaning post into understanding.

Top Left: The discovery monument for Wocka Blue Rocks (look for the jar which contains the Notice of Location). Top Right: The Northeast Corner marker. Bottom Left: The rocks are blue, our cat is named Wocka - Wocka Blue Rocks. Bottom Right: Yours truly enjoying a day of mining.

Assorted discovery and corner markers (I have literally thousands of photos of these - probably should just make a standalone catalog of them).

Witness Posts

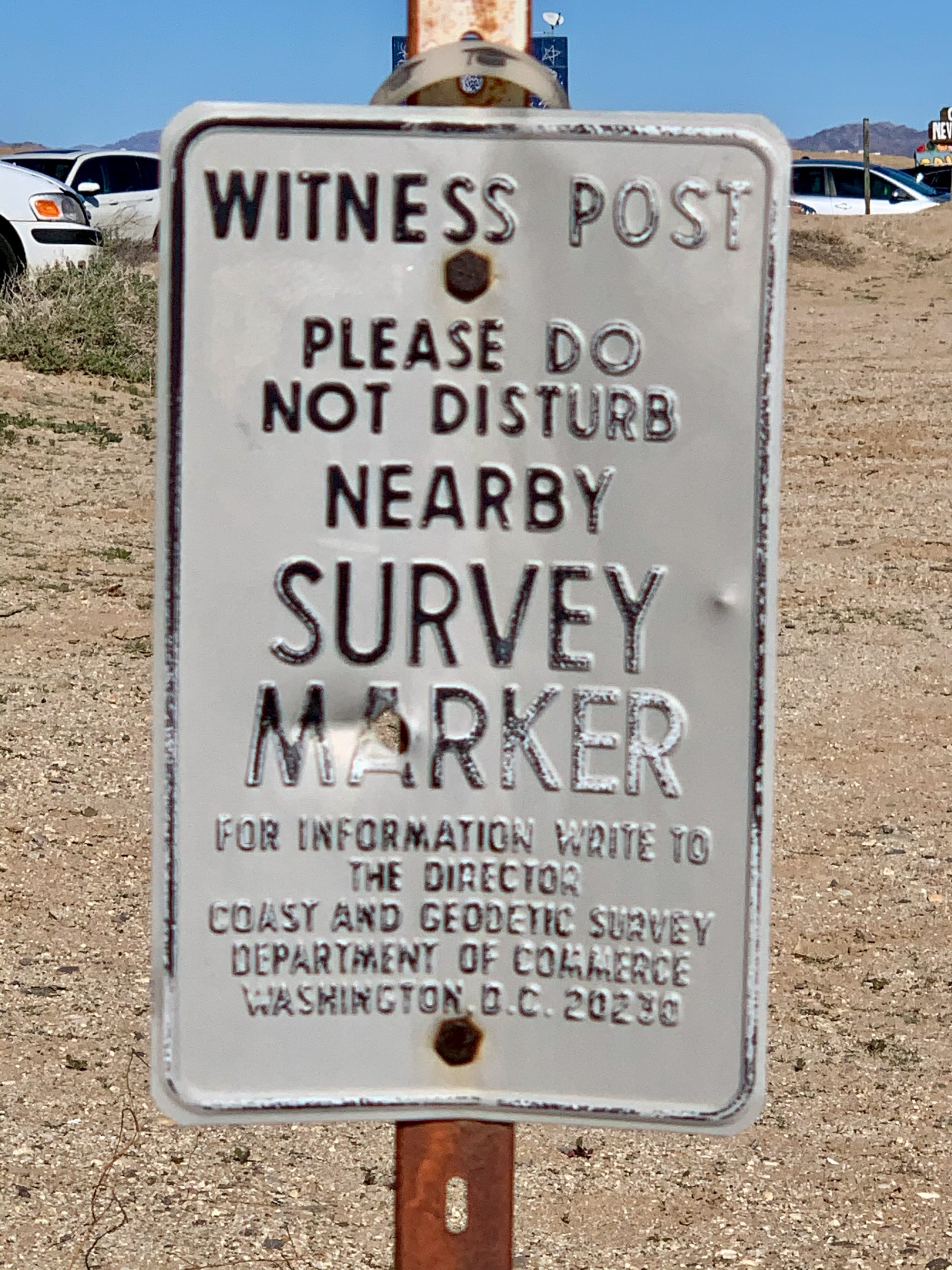

Among the various survey markers scattered across the American landscape, witness posts are often overlooked but play a crucial role in land surveying and boundary identification. Unlike benchmarks or mining claim markers, a witness post does not mark the exact location of a survey point. Instead, it serves as a reference point for a nearby but possibly hidden or inaccessible monument.

These posts help surveyors, land managers, and explorers locate official survey markers that may be buried, obscured, or otherwise difficult to find. Understanding witness posts can be the key to deciphering old survey records and accurately navigating historical land divisions.

Witness Posts – Marking the Location of Hard-to-Find Monuments

Purpose:

A witness post is placed when a primary survey monument—such as a section corner, quarter corner, or benchmark—is difficult to locate, missing, or needs protection from disturbance. It serves as a nearby reference point that helps direct people to the true survey marker.

Key Characteristics:

- Does not mark an official survey point but points to one nearby.

- Typically made of metal, wood, or plastic, with signage explaining its purpose.

- Often painted bright colors (yellow, orange, or white) to make it visible.

- Placed a short distance (a few feet to several yards) from the actual survey monument.

- May include an arrow or direction indicator pointing toward the true location of the survey point.

Where to Find Them:

- Near section corners and quarter corners in remote or overgrown areas.

- Along roads, fences, or property lines, where a direct marker might be at risk of removal or damage.

- Near benchmarks (BM) and vertical angle benchmarks (VABM) that are embedded in rock or set in hard-to-reach places.

- On modern public land surveys conducted by agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or U.S. Forest Service (USFS).

Why Are Witness Posts Used?

Surveyors place witness posts for several reasons:

- Preservation: In areas with frequent human activity (roadways, construction zones, trails), the actual survey marker may be buried, covered, or removed. A witness post helps prevent accidental destruction.

- Accessibility: Some survey markers are placed in difficult-to-reach locations (such as steep terrain, rocky outcrops, or under thick vegetation). A nearby witness post makes them easier to find.

- Survey Verification: If a section corner or other key marker is missing, a witness post can provide a reference point to reconstruct the original position based on survey records.

Why These Markers Matter Today

Though witness posts might seem insignificant at first glance, they are vital to land survey integrity. A witness post can help surveyors and land managers relocate historical survey points, ensuring that property lines, land ownership, and public land boundaries remain clearly defined.

For explorers, finding a witness post is often a clue that a more important survey marker is nearby. Taking the time to look in the direction it indicates may reveal a forgotten benchmark, a mining claim corner, or even a long-lost section corner—pieces of history waiting to be rediscovered.

Various examples of witness posts.